The advice in this post is just so marvellous I have just purchased her book on story structure and the accompanying workbook. Ms Weiland offers succinct advice not only on what to avoid, as well as why to avoid it and what it does to your narrative. I honestly could not have put it better. Rather than rehash the whole article I will summarise her main points, add my own input and examples, and link back to the original at the bottom.

Shall we begin?

The breadth of description required of written prose is vast in comparison with visual media. However, the author is both guide and gatekeeper to the narrative description, deciding what the reader needs to know and when. Authors are also human and, as such, we like to play with the details and show off. This is true whether we write for fun or publication. The fact remains that if we wish our writing to improve there are four habits we must consciously learn to avoid.

- Looking too deeply at the relationships between minor characters. However close the attachment, or tense the conflict, the relationship between the minor players need not get a mention unless it has an effect on the plot. if you want to explore it further you can always take a leaf out of the likes of Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Shadow) or Anne McCaffrey (Nerilka’s Story) who have written whole versions of their works from the perspective of minor characters

- Travelling filler and uneventful journeys. Don’t try to stage direct an empty theatre: you’ll bore yourself as well as your audience.

- Repetition of conversations already witnessed. Say you were at a party, but one of the guests was reciting back to you a discussion you had already heard. You’d get bored pretty quickly right? So will your readers.

- Information-dumping. If you have found out something really interesting, and you just have to share it, use an end note (not the same as a footnote). It’s what they’re for. This way, you can still demonstrate the level of research you have put into your book, but you don’t have to break your narrative, and the reader gets a choice whether to read the proffered information or not.

Unnecessary scenes damage your story in several ways.

- They bore readers. Just like the way an advert break during really good film right before the climax could put off a viewer and make them change the channel, an info-dump or disjointed tangent will make them simply put the book down. Worse? It could make them avoid your other or future titles.

- Misdirection for dramatic effect. Don’t be the taxi driver who goes the long way around just because they want a bigger fare (we’ve all met at least one). Your reader is your passenger. They don’t need to know what the field they are passing looks like, or what people are doing at the side of the road unless it has something important to do with the story (disposing of what could be a body?). Deliberate red herrings are an old fashioned, cliched device and have very much gone out of fashion.

- Derail narrative. On the theme of minor-character relationship-overshare: narrative prose is not the same as a TV program where all speaking-character relationships must be visible and clear from the off. Unless the feelings your main character has towards the ever so dishy, leather clad pirate (Once Upon a Time) have a bearing on the direction of the plot (they get there eventually), they need to be left out. In Speaker for the Dead, Novinha’s love for Libo (who does not take an active role and appears mostly in reference) causes her to lock her files and hide the results of her experiments for fear that he would make the same discovery that had cost his father’s life. In this case, withholding that information did not have the desired effect, but the story would not have made sense without it. However, it could have easily been overdone, and I have seen it overdone time and time again (*cough*, Sword of Truth Series, *cough*)

- Fragment the story and distract your reader. If a scene does not fit, it can wreck the whole cohesion of the book. Keeping unnecessary scenes is like trying to add extra pieces to an already completed jigsaw puzzle just because you happen to like the colour contrast. Not only to they not add anything substantial to the picture as a whole, but they can detract from, hide, or even break up the other pieces.

Here is how to avoid these errors.

Plotter or not, once you have completed your first draft (not before) you will have to go through your novel from the perspective of a reader, but before you delete anything, save your book under a different name (2nd draft?), that way if you want to recover something you have previously deleted and paste it in a later part of the book, you will be able to.

- Mentally delete them. One by one, go through and look at every scene. Can your story survive without it, in regard to character development or plot cohesion? If so, delete it. You don’t need it.

- Sweep for opportunity-darlings. Those little nuggets of ‘narrative genius’ that occurred to you as you wrote but somehow slipped past your mental outline-guards? Get rid of them. If your story can survive without them, in regard to the criteria in the previous step, then they are gatecrashing your party, abusing the free bar, and need to be thrown out. Hint: they’ll be more common in the messy middle.

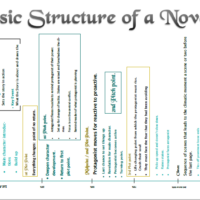

- Good use of scene structure. Here, I refer you to Ms Weiland’s guide to scene and sequel construction which can be found by following the link below. You’ll also find the Amazon.com link to her book.

Source:

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 40: Unnecessary Scenes – Helping Writers Become Authors