by Anna Johnstone | Sep 25, 2017 | Advice, Service

A lot is said about how to find the right editor for you but today’s post is about being a good client. I had not intended for this to be this week’s post but given the circumstances, I thought this needed to be said.

Most of us know by now that the business relationship runs both ways. It should be one of mutual benefit and courtesy. Most of you know you need to be polite to editors when introducing your work, and they know to be tactful and treat your work with respect and discretion. Most of you know that most editors are very busy and cannot simply drop everything to make your work an immediate priority, but we still try to be polite when dealing with even the most ‘urgent’ projects. However, there are times when we meet those who don’t know these things, and today was one of them. I would like to draw from my own experience for an example of how not to introduce yourself to an editor. I will not name names. Doing so would be unprofessional and serve no purpose other than to exacerbate the problem, However, I do not feel that ignoring this experience will do any good either. For the moment there are two things authors need to remember;

- Good customer service does not mean being a doormat and accepting poor treatment just to get the client. Good customer service requires effort on behalf of the client too.

- Editors talk… A lot… About everything…

A few days ago I received an unsolicited ‘friend’ request from a member of one of the many writer’s groups I am a part of on Facebook. Recognising the name and thinking it’s about editing as it came on that profile, I accepted it and sent an invitation to my editor’s page to let them know it is there. This is not the same as a ‘request’ and people are free to decline it. I had thought nothing of it since given that my service has been closed for the last few days following the sudden death of my father. It strikes me that if he had really read my page he would have seen my pinned post. I digress…

Today I have experienced possibly the worst example of entitled behaviour since I started fourteen months ago. I arrived at my page to check my messages to find a personal message (not to the page, but to me personally) to say that they had liked my page and would I now like theirs “Only if deserved”. I didn’t get a chance to tell them that I was rather busy and would take a look when I had time because when I gently pointed out that my service page does not engage in like-swapping he began hounding me to just follow the link to his page and hit ‘like’ (even the most technologically naive of us should know not to ‘just follow’ any link.) just because he had liked mine. He had not used my service or put work my way so I am surprised he did. When I told him his behaviour to me was aggressive, he threw a tantrum that would have embarrassed Super Nanny; accusing me of spamming him, even though I explained that the invitation was only that; an invitation, and telling me not to buy his book. At no point did I say I would not like his Facebook page, but I was not given the opportunity to say that I would take a look when I had time because I was blocked before I could and simply because I would not drop everything and give him exactly what he wanted when he wanted it. He wanted me to like his page as an endorsement to his work without ever having read it.

In a way, I am sort of glad that this client has exposed his nature as a difficult client before I had to deal with him. This person is not the type of client this service is looking to engage with. Nor will it be. Ever. What did he do wrong, you ask? Firstly he assumed that he had an automatic right to my time and attention and that I should be grateful for his and jump to his will. It would take me time to go to his page and read his work. Time that I just don’t have this week. Yes, his primary introduction was fairly polite but his tone and demeanour changed to one of affronted aggression the moment things did not begin to happen exactly as he would like. That was his second mistake.

Remember, that editors are more than merely a living spell checker. We have lives and we have self-respect and we talk to each other. We know who the merely difficult clients are. We also know who the ones to avoid are. This is the beauty of being a freelancer. We have the privilege of choosing who we deal with. Imagine he had behaved that way to waiting for staff or someone at a call centre who did not have that option? It is not okay to treat anybody that way and if the cost of not putting up with it means one less rude or difficult client then that price is worth it.

by | Apr 7, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Proofreading and copyediting, while not nearly as entertaining as the writing process to some (a lot of us quite enjoy it), is still important. For many authors who don’t outline editing is a chance to iron out plot holes and check character arcs. For others, it’s a chance to flesh out some parts you might rush through just to finally finish creating the bones of the story but that’s the bigger picture. This post covers some of the reasons why DIY editing, is not always a good idea. There is no substitute for properly and carefully checking your own work for errors or, if the mere idea of proofreading sends you straight to the Land of Nod, hiring someone like me.

1. It won’t catch caption errors, transpositions, inconsistent formatting or repeated text.

There is no way around it. So long as you’ve spelled each individual word correctly, it will not bring it up. The red and blue squiggly things in Word are a guide but they are only as reliable as to human being who programmed them. A spellcheck is set to look for individual words but it doesn’t always see them in context. Typing ‘form’ instead of ‘from’ won’t be picked up as an error. A spell checker is no substitute for knowing the rules of grammar and punctuation. How will you know if the suggested change is correct if you don’t understand how commas work in the first place. You’ll never catch every mistake on your own, but you have a good chance of creating some new ones if you rely solely on the automatic functions of your word processor.

2. Proofreading is more than a manual spell-check.

This is the last stage of editing prior to publication. It’s vital not to leave this stage to chance. It allows you to look for colour variations, layout issues, spacing, typeface consistency, missing items, tense and tone errors, content errors, inconsistent capitalisation, that page numbers are correct, and other formatting problems. In short, this is your polish. No matter the content, presentation matters and sloppy presentation will come back to haunt you.

3. It can’t check for flow, or that the language style suits your audience.

It won’t be able to tell whether your content delivers the content promised in the title. Does the writing style of the meet their expectations? Are the facts correct? If it’s an academic work, are those facts supported by cited evidence? If my spellchecker had been able to check references, I would have had a lot fewer headaches while I was studying for my degree but I would have still checked them for errors myself.

4. It cannot fact-check.

Given enough time to do their homework, a good writer should be able to write about anything. Problems occur when guessing comes in and spellcheck won’t be able to check for accuracy, homophones, mixed metaphors or awkward similes.

5. Over-familiarity with the text.

You’ve been staring at your essay for days. Constructing arguments, deconstructing sources, and now you are finally able to submit your assignment to your tutor. This is the trouble. You will read what you expect to see on the page and this will lead to errors being missed. Even leaving it for a few days will not entirely eliminate this problem. Human memory cannot be trusted. This reason alone is reason enough to recruit an extra pair of eyes. Couple this with the limited ability of your average built-in spell-checker and you have the ideal conditions for missing some very embarrassing gaffes.

![How to be a good client.]()

by | Mar 26, 2017 | Advice, Blog

We’ve all heard of that one person who demands more from a service than is strictly reasonable, haven’t we? They want the dry cleaner to somehow get the turmeric stains off of the front of their favourite top and then scream blue murder if they – unsurprisingly – fail. They expect freebies, discounts, and are rude to waiters. They delay paying a bill for something because they’d rather go down the pub. They’d even go so far as to make a spurious complaint on the off-chance that they could save a few quid, never mind the effect that complaint could have on another person. Okay. These are extreme examples. The point is that while we expect to get our money’s worth out of a service, a healthy business relationship is a two-way street. In light of this, here are a few things to bear in mind in order to not be that customer.

Always prepare a brief.

We love these. These tell us exactly what is expected of us and enable us to realistically price and plan your project. A brief to an editor should include the following information.

- The title of the work and the author’s name and contact details.

- How many files are involved and what they include.

- The nature of the work. Is it a novel, an essay for assessment, an article for a magazine etc.? This helps us assess if we have the necessary skills to complete your project. Some editors specialise in fiction in a particular genre so sending them your dissertation on the history of the paperclip (gripping material) would not do you a lot of good.

- The deadline and when you expect the project to begin. This editor might not be available at the time you need them. If you ask, they might be able to point you in the direction of someone who is not only available but shares your obsession with stationery.

- The length of the document. This will affect the pricing of the document. Your editor needs to factor their time into the equation.

- Is it a blind edit? If the document has undergone editing prior to your project, you may want to send the original as well as other documents so that this editor can see what changes have already been made. You don’t want them undoing the work of another. It’s a waste of their time and yours.

- The style guide or house style you are working from. Send them a copy so they can familiarise themselves before starting work.

- The level of intervention expected. Don’t be the client that asks for a copy edit but expects the whole thing to be rewritten. This part of the brief allows the editor to clarify which parts are part of the normal service and which bits are extras. You will be expected to either sacrifice extras or pay for them. Similarly, you might only want to check for spelling, grammar and typos.

Your editor has many talents, but mind reading is not one of them. The brief above is the bare minimum of the information you should expect to provide. Being clear from the beginning will help avoid any nasty surprises later on. It will save you both time,

The price may be negotiable but an agreement is an agreement.

Many editors now will issue a service agreement relating to the final negotiated terms of payment. These include the services expected, sometimes in great detail, so be sure to read them thoroughly before sign anything. It also includes the rate that you have agreed to. This agreement stage protects you as much as the editor but while it constitutes a promise to carry out x, y, z, it also constitutes a promise from you to treat the service provider fairly.

A service agreement will, at the very least, include the rate that you have agreed to pay, the services to be carried out, deadlines, and the dates by which it is to be paid. You might have arranged an instalment plan. If so, you have a responsibility to make these scheduled payments at the agreed time. It will likely list any penalties and consequences for not meeting your side, as well as what they are prepared to do in the event that they fail to fulfil their end. If you do not feel these are fair then you should not sign the agreement. Attempt to negociate terms but be fair. You cannot expect them to remove anything that protects them.

Asking for extras mid-project is another danger area. For instance, if you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, would you not? The rule is the same for services. If you want extra, this may often mean amending and signing the service agreement to reflect the changes. You can be a good client by

- Asking if it is feasible to extend the length of the project. Your editor may not have the time. Some of us work on more than one project at once while others prefer to concentrate on one project at a time. We all work differently so you should double check that we are available before giving us extra work.

- Ask how much extra it will cost. If you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, wouldn’t you? The same applies to services. Similarly, if you found that you had left something out of your brief, and it hasn’t been done, you would not complain that the editor did not fulfil your brief.

- Paying as promised and on time.

Trust

This works on both sides. You need to trust that your editor knows what they are doing and that they can deliver the service to the promised standard. They need to trust that you will uphold your end of the bargain. No matter who much you like an editor, if they feel that you have acted unfairly, they may decide that the stress of working with you is not worth the price.

You chose your editor because they possess a skill set that you do not. For this reason, alone you should listen to them. Give them the freedom to keep their promises to you. Editing is a collaborative process which takes both time and care. If they come to you with a query, answer it promptly and politely. It is true that anybody can call themselves an editor, and unfortunately there are cowboys and charlatans in every walk of life, but the good ones know their craft. Treasure them. Many are published authors in their own right so have experience from both sides of the relationship and empathise with your anxiety. They also take pride in their work and want to help you make the best of your work. It’s not just about making money.

Professional pride

Like other services, our living relies upon our reputations. There is a fine balance between personal opinion and the decisions formed by experience and skill. If your editor feels they are unable to point out flaws in your writing, due to the reaction it might induce, they will not be working to your best advantage. You want your editor to pick up problems and bad habits. It’s how you will learn to be a better writer. So while an editor might exceed their remit in some cases, remember they are doing the job to the level that they would eexpectto receive it.

Back to the dissertation analogy here. Say you handed them your brief to check spelling and punctuation only, but the editor noticed that your use of paperclip vs. paper-clip was inconsistent, but because they had not raised the issue or highlighted them, you were marked down by your tutor. And what if the reason they had not mentioned anything is becasue you had refused to accept input over the wording. This would not be what the editor would regard as a successful outcome even if they had fulfilled the terms of the brief to the lettter. This can be avoided by

- Being flexible with your brief. If you have left something off and the editor raises the issue, it is usually because some part of your writing has raised a concern and they could not, in good conscience return the editied work without raisning the issue. This is a good thing.

- Ensuring your brief includes everything you want from the service. It is also way the pre-project discussions are so important.

Reasonable deadlines

It doesn’t matter how fast someone reads...Scratch that. It matters a lot.

Proofreading, in particular, means slowing… right… down… and taking in every word carefully. It means looking for extra tall lettters hidden with others, because the human eye is a lazy beastie and will assume that what it sees is what is really there. Reading a two hundred page novel might be possible in two or three days, but editing is not the same as reading for pleasure. Often, it means checking that all captions match images and bibliography formats are correct, looking for double spacing, transpositions, or repeated text. In other words, it means doing what the spell-checker can’t do; apply common sense. This is also why you shouldn’t just forgo editors and rely on the spell check. The spell check can’t find plot holes. It is vital that you apply common sense and allow adequate time for the work to be carried out. A betaread of a 85k word novel could easily take two weeks due to the level of care needed in the reading.

Leave fair and honest feedback; spread the word

If you are happy with the service you have recieved then say so. Frequently. Recommend them to colleagues and friends. Way back before the internet, businesses lived and died on their reputations. Today, this is even mor the case. The rise of social media means that the lack of pressence and reviews is almost as bad as negative reviews. It tells future clients that this person cannot deliver what they promise. It’s like the boss who ‘loves’ you right up until you leave, then refuses to give you a reference. Reviews are the references of the information age. Use them. Tell the world you love your editor and why.

The other thing not to do is to leave vaugue feedback, or comments which contradict your repsonses to the editor. The feedback is not the place to bring up new problems. It is the place to tell people how well your editor did their job including dealing with a misunderstanding over style. Your editor relies on feedback to not only gauge reach and reception, but to iprove their service. It is important they these be honest. A dishonest negative review can do someone real harm, they are not funny or ethical. If your editor has failed to meet a deadline or fulfil their side of the agreement, AND THEN failed to deal with the situation adequately, then by all means take to their facebook page and lambast away. At least initially, you should deal with greivances calmly and in private.

by | Mar 9, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Authors,

I ask now for you to put yourself in the role of a freelance editor. Now, imagine a situation whereby a client approaches you, accepts a quote, goes through the sample edit process etc, and after a week of schedule-juggling, they promise to send the rest of the service agreement paperwork back to you that day. All good so far. Now, consider how you would feel if the job you had worked extremely hard to win was suddenly taken from you because the cancelled on the grounds that a quote your client has just received another quote for ‘considerably less’ than the rate they were expecting to pay you. While the second editor in the above scenario may have had no idea that a contract and a price had already been agreed (bar signing on the line), the author most certainly did know and actively chose not to disclose the fact. They choose, instead, to disregard past promises as and when they saw an immediate advantage. Is such a person likely to prove trustworthy in the future? Unlikely, and I would caution editors away from future professional engagement with those who have acted in such a manner.

When you take on an editor, you are entering into a business relationship which requires a high level of mutual ethical conduct and trust. This relationship is far more formal than that of a consumer/retailer or service provider. In a business relationship, there are some basic rules which determine its success. One such rule is to treat others with the same honesty, respect fairness that you expect to be treated with. In business, all is not fair. A promise is a promise and honesty is always the best policy. If you are an author and find yourself in a situation where you must make up a story in order to get out of a promise or an obligation, the likelihood is that you already know that you are behaving unethically. Would you take on an editor with a reputation of behaving dishonestly?

The indie author community is growing but is still fairly new. You know the constant uphill struggle of finding editors and agents willing to take you on. The struggle is the same for editors who are trying to make a living in an industry with limited cash flow. That said, most of us will not willingly undercut one another, or poach clients. If given the full facts the above latecomer would probably walk away. The author opted to deny them the opportunity to make an informed choice. Writers and the creative community as a whole have a responsibility to display demonstrable honesty in our dealings with each other and treating even freelances editors poorly, or sowing mistrust between us, will reflect badly on the emerging industry. It could even be used to justify the remaining prejudice against self-published authors.

My advice if you ever find yourself in the above situation as an author is that if a late quote comes in after you have made a promise, then it is the ethical decision to thank them but let the latecomer know that you have already accepted another editor. You don’t necessarily have to let them know what you are paying, but give them the opportunity to step back. If they then try to undercut the accepted offer, you will know what sort of person you are dealing with. Deception by omission is still deception, and clients can earn a reputation for bad practice as easily as editors can. Think carefully about how you conduct yourself. A good editor, treated well could last your entire writing career. Treat them badly and you could end up with a long list of people who simply will not work with you.

by | Feb 9, 2017 | Advice, Blog, Service

This is just a quick note to readers to let you know that I haven’t forgotten you. For the last two weeks, I have been lagging under the weight of a really nasty flu bug and yesterday was a really bad day, and it’s on that note that I write this post.

Let yourself have a break. Nobody is going to sack you and tell you to clear your desk you for not feeling up to it. Writing should not be a chore we have to force yourself to do no matter what. If it is, then you are doing it wrong. I’m guessing, due to the fact that you are reading this, that you are creative people. That creativity is not going to fade because you took a day off to recover from being ill, or you had to look after a poorly child. So if you need to, take a step back, do what you need to do to enable you to be able to come back with a fresh head and enjoy what you are doing.

One of the first stages of Harry DeWulf’s Readworthy Fiction Course (Fab course. I highly recommend it.) is to look after your personal comfort and finding the best set up for you to write in. To me, this includes allowing the writing process adequate head space. If you have a list of stuff that you have to do niggling in the back of your head? You are not comfortable. Go do that stuff, get it out of the way, and use the boring housework time to think about your story. Some of my favourite ideas have come while clearing up Lego (I have 3 boys under 8, therefore I am doomed to do this for at least the next ten years). If you are full of cold and feeling rubbish? Don’t even try to do more than scribble down ideas. You are best off looking after yourself. Have a bath, dose yourself with hot tea and cold cure and, as Joanna Penn would say, do something to “fill that creative well“, (I love that phrase). Believe me, trying to write with diminished concentration will not do your work any favours.

Look after yourselves. With any luck, I will be back to feeling up to writing two posts a week from next week. Thank you for your patience.

by | Feb 8, 2017 | Advice, Blog

“Using the outline to figure out the technicalities of your plot gives you the freedom to deeply explore your characters, settings and themes in intimate detail in your first draft.”

– K. Weiland | Outlining your Novel: Map your Way to Success –

By using brief bullet lists to sketch out the order in which events in our story takes place provides a map. It doesn’t have to be laden with small details and contrary to popular belief, it doesn’t have to take as long as writing the book BUT a succinct outline will help identify and gaping holes in your plot and enable you to fix them before you start writing.

A rough outline will also allow you to regulate the pace of the story, set up the tone for the next chapter, and get a general idea of what fits with what, on a step-by-step basis. It keeps the story from drifting away from you and enables you to weave in a couple of complimentary sub-plots, making sure you use adequate foreshadowing for plot twists. My advice on sub-plots is to keep them to a minimum. Too many and you risk crowding- out the main plot. If you are going to use sub-plots, you need to be as consistent as with the main plot (beginning, middle, end) as you are with the main plot or you will leave your reader wondering what happened to characters who just seemed to vanish.

The length of an outline will vary between authors. It really is up tp you and there is no strict set of rules to follow when planning. Some will spend weeks planning every detail of their world. I am finding that I prefer to map out the direction of the story then fill in the details as I go. It gives me the best of both worlds. They don’t need formal formatting because that information is for you (Who else is going to see it?). It doesn’t mean anything is set in stone either. If you feel that something else will work better, then use that idea. It’s your work. K.Wieland looks on an outline as a barebones first-draft, and I tend to agree. It’s merely a frame, not a rune covered cairn stone which must be obeyed like you have made a pledge to Odin. It’s the ideal place to make your mistakes because here they are easily corrected, and invisible to the reader. You can lay down the foreshadowing of events and see at a glance if your chapters are missing anything before you even start writing.

What do I need?

A general rule of outlining is that there is no, one set of kit or right way to do it apart from the one that works for you. It is a trial and error process that only you will be able to find for yourself. You might even find that your preferred method just isn’t working for you and have to find another. Chapter 2 of K.Weiland’s Outlining Your Novel looks at some of the means of planning available to most writers, as well as the approaches. Like Ms Weiland, I prefer to take myself away from the screen and distractions (Okay, Facebook, Twitter and Spotify. I’m human.) and write my ideas by hand in an A4 spiral bound notebook. This is also a really good excuse to treat myself to some of the pretty stationary from Wilko’s. It makes me slow down and consider the direction of the story and gives me an instant hard copy safe from glitches and fatal errors which can so easily wipe your work from the face of the earth.

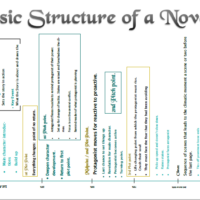

One tool you do need is an understanding of dramatic structure. No matter how exciting your story’s basic idea, an incomplete view of how a story is put together will take you round in circles. You might think you are being rebellious and daring by refusing to adhere to a ‘formula’, but if you don’t know how a story structure works, what are your rebelling from? Even the impressionist painters of the 19th century knew how to ‘do it properly’ before they started playing with techniques and new styles. Read books, take free courses, test yourself. Do whatever you need to in order to understand this. A copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms is an invaluable source in this learning process.

Larry Brooks describes six ‘core-competencies’ within the craft of storytelling. One of these is structure. The others are

- Character

- Theme

- Scene

- Execution, and

- Voice.

Your job as a writer is to get good enough at one of these that you stand-out in a crowd of thousands with the same skill-set as you.

No mean feat and I applaud you for taking on the challenge. Here’s the bad news: It’s going to take practice and planning, work, and possibly years, to achieve this. There is no short cut.