by | Jan 20, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Writer’s First Rule.

People pay you for your work. Not the other way around. If someone asks you to pay money, ANY money, in order represent your work you need to do several things:

- Tell them you are no longer interested

- Block their number

- Add their email to your ‘blocked senders’ list

Preditors & Editors was an excellent source list of the good, the bad, and the evil in the world of writing services, but unfortunately, it appears to no longer be active.

The advance.

The sum that the publisher pays you which reflects expected sales. Unless you break the contract that’s yours regardless of how well your book sells

Earn-out

Well done. Your book has earned back your advance and then some. You now get to keep your royalties.

Rights

This is the permission you give to the publisher to publish your work in a specific form, language and place. A legitimate publisher will pay you for these rights as part of your contract, but not on a permanent basis. At the end of a set term they revert to you and if that publisher wants them back, they have to pay again. Do not sign any contract which gives the ‘publisher’ permanent rights.

Royalties

A payment structure which offers a percentage of each sale to you. An average figure would be 6-9% for paperback and 10-12% for a hardback. Ebooks earn a whopping 25%. Often the rate increases as more are sold. It is vital that you get a regular statement for these.

Getting paid

The publisher will give you an advance based on what they think they can sell, then royalties on each copy sold. If you have an agent, you will have to pay a small percentage in return for representation. Your royalties should be paid on at least a six-monthly basis from a large publishing house. Smaller ones may have a shorter schedule.

A £10k advance (lucky you) to sell your hardback novel at £10 each at a rate of 10% would earn the writer £1 per copy. They would have to sell 10,000 copies to earn out that advance. Selling anything over 10k copies is when they start paying you the rate switches around and the publisher gets £1 per copy.

Writer’s Second Rule

The agent only gets paid based on what you sell. You do not pay an agent to represent you. 15% is about average. and they don’t get paid until you do.

There may be odd business tax expenses that you need to take care of but these are infrequent and not the same as fees.

What are agents for?

- Handling contract negotiations

- Submissions of manuscripts to editors. Many of the big publishers do not accept manuscripts without an agent. You may struggle with this without an agent.

- Career advice

- Troubleshooting any problems between publisher or editor and you.

- Handling foreign rights, TV, film etc.

- Some might offer editorial assistance

How involved the get will depend entirely on the agent. Always be sure about what you want, and that they are prepared to provide it. If they want 15% of your hard earned royalty, they must earn it. Whether you opt for an agent is entirely up to you. Do not be tricked into believing you must have one for ‘legal reasons’. Anyone can hire a solicitor to look over a contract, but this is a one-off expense and it won’t mean giving up 15% of your sales.

How do I catch one?

You will need to write a convincing query letter along with a sample of the manuscript. Remember the agent won’t get paid unless it sells, they are going to need to be convinced that their time and effort won’t be wasted on a dead-parrot. If an agent accepts straight away or asks for a fee, walk away.

Writer’s Third Rule

Never pay a publisher. A publisher’s role is to print and sell books. The honest ones pay writers to produce work to print. If they ask you for money, run away. These publishers either have no ability or intention to provide marketing or distribution because you have already given them what they are looking for. Money. You would be better off doing it for free on Amazon, a free WordPress blog to serve as an author website, a free facebook page and a twitter account. Be aware that self-marketing without paid advertising is very time consuming and labour intensive (take it from someone who has been working their socks off trying to get a new start-up off the ground for the best part of a year).

Editors.

- Hired by a publishing house to buy the manuscripts for print and sale, or

- Freelancers who help writers get their work to a level where it is fit to be published.

Publishers’ editors are paid by the publishing house, not you, and will work with you until they are happy that the work is saleable. They are responsible for the quality of the finished product.

I am in box number 2. We’re hired by writers to help get your work to a standard where it can be sold. On average you can expect to pay between £25 and £100 per hour for their time and skill. Many of us prefer to charge by word count as it is never clear how much work will be needed on an individual manuscript. If you are looking to publish traditionally, you do not need to hire an editor to get the book ‘ready’ as the in-house editor will do that, but you will need to be certain that the work is of a professional quality. The publishing house should not be asking you for any money to do this work.

If you are looking to publish traditionally, you do not need to hire an editor to get the book ‘ready’ as the in-house editor will do that, but you will need to be certain that the work is of a professional quality. The publishing house should not be asking you for any money to do this work. If you are looking into self-publishing, then an editor is a must. A bad or cheap edit will stand out a mile.

You are not looking for cheap here either. Look at testimonials, look at their websites etc. If they are dirt cheap and have no testimonials, there will be a good reason. If a freelance editor demands more than a 50% upfront deposit, do not hire them.If they don’t offer free samples or refuse to offer a service agreement, these are also red flags.

Self-publishing is not the same as ‘vanity-press’.

Thankfully the stigma of self-publishing has somewhat decreased in recent years, and it has been made easy what with the rise of Amazon Kindle, iBooks, Kobo, Smashwords and Createspace et al. which are generally free except in terms of time and effort. Traditional publishing has been known to take in excess of a year to get books from the author to the page and into the shops. The cost of self-publishing comes in the fact that you are in charge of your own cover, editing, marketing etc. There are also no advances. On the other hand, royalties are paid monthly, come at around 70%, you retain all the rights. It is very important to read all of the terms and conditions before signing up to any of these services. Exclusivity deals, while on the surface might look fruitful but be aware that in recent weeks Amazon has been known to delete whole accounts on the basis of a suspicion. You will have to look carefully into all your options before deciding which route to take.

Sources

More on editors etc.

by | Jan 18, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Last week I talked about unnecessary content and scenes which do not drive your story ahead. This week I am going to continue on that theme because I cannot stress enough the importance of clarity. While a good structure is vital, don’t be in too much of a hurry, or try to race through to the end. Writing is a hike, not a 100-yard dash. Hiking means being able to take in the surroundings, enjoy the autumn colours, spot wildlife, and properly stretch your creative legs. Doing it at a flat-out run means indistinct settings and unclear description. By trying to go too fast, you risk missing out details which help to set the scene. It will not make your reader more alert but lead them to ask the wrong questions about your narrative. In turn, being vague or indistinct means you are leading the readers’ attention away from what they need to know about the story, and missing out on an opportunity to build some depth into your characters through observation of their reactions.

Look at the following examples from K.Weiland’s ‘Most common Mistakes’ post from 2011:

- Maddock looked at the wall, which seemed to be smeared with spaghetti sauce.

- The bomb fell approximately ten or twelve feet away from me.

- Elle was about forty-five minutes late for her dentist appointment when a cop pulled her over, apparently for speeding.

- Mark’s figures revealed that the addition to the house would take up roughly fifty square feet.

Do any of them really help you to set the scene or give the reader a feeling that they need to know this? Nor me. It makes me think this is just filler. Why is the author wasting my time in telling me this? Take out the supposition and the approximation, then we know that the information is important and we will probably need to remember it later. Being unsure of the measurement of the house could prove very expensive, but being definite about it has us asking, why he wants to extend? Is Mark trying to hide something? Is he building a secret den? We know when something comes out flat. It feels trite or contrived; as if it could really be done away with. Being vague has the same effect. If that information is important then the ‘seemed to’, estimations, and approximations need to go. Your author voice will come through the stronger for it.

Sometimes, however, you will need to guide the reader or drop hints about the action or something the main character has observed. There are ways to do this but many of them are wrong. K. Weiland has again offered us a handy list of words to avoid:

- Seem

- Approximately

- About

- Appear

- Look as if

- Roughly

- More or less

- Give or take

- Almost

- Nearly

Persuasive, and evocative descriptions are a vital part of any narrative. Being vague is apologising to the reader for knowing more than they do, or trying to point something out and trying not to sound too clever about it. Stop apologising. Your job is to direct the gaze of your readers. Do not hesitate to give a full sensory experience. In a crime scene, for instance, your main character would be looking for clues. Your reader will be asking what did the air smell of (decay?) or was there a lot of blood or how far the deceased’s head had landed from their body (have someone use a tape measure). ‘Seemed to’ writing will only serve to diminish their experience, as well as rob at least two people of the experience of imagining it. This is not to say that you cannot use metaphor to transmit your meaning, but be cautious. There is the risk that you, as a new writer, will be tempted to hold your reader’s hand and explain them. Don’t. If you have got it right, the reader will understand it. Likewise, if you show your reader what is there, then they will see it.

Sweeping statements and generalisation is another form of dithering to look out for, and eliminate. You don’t need to make sure the reader ‘gets it’. Long winded justifications of your action won’t achieve this either. By going around the houses in order to set the scene you risk boring your audience with the minutiae and they will miss things they are meant to see. It also hints that you are unconvinced by your own story. The message here is to slow down. Be bold enough to say precisely what you mean and what you want your readers to see. Your readers will thank you for it.

Sources

by | Jan 11, 2017 | Advice, Blog

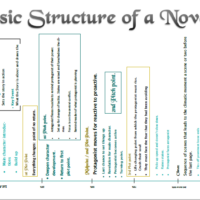

The advice in this post is just so marvellous I have just purchased her book on story structure and the accompanying workbook. Ms Weiland offers succinct advice not only on what to avoid, as well as why to avoid it and what it does to your narrative. I honestly could not have put it better. Rather than rehash the whole article I will summarise her main points, add my own input and examples, and link back to the original at the bottom.

Shall we begin?

The breadth of description required of written prose is vast in comparison with visual media. However, the author is both guide and gatekeeper to the narrative description, deciding what the reader needs to know and when. Authors are also human and, as such, we like to play with the details and show off. This is true whether we write for fun or publication. The fact remains that if we wish our writing to improve there are four habits we must consciously learn to avoid.

- Looking too deeply at the relationships between minor characters. However close the attachment, or tense the conflict, the relationship between the minor players need not get a mention unless it has an effect on the plot. if you want to explore it further you can always take a leaf out of the likes of Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Shadow) or Anne McCaffrey (Nerilka’s Story) who have written whole versions of their works from the perspective of minor characters

- Travelling filler and uneventful journeys. Don’t try to stage direct an empty theatre: you’ll bore yourself as well as your audience.

- Repetition of conversations already witnessed. Say you were at a party, but one of the guests was reciting back to you a discussion you had already heard. You’d get bored pretty quickly right? So will your readers.

- Information-dumping. If you have found out something really interesting, and you just have to share it, use an end note (not the same as a footnote). It’s what they’re for. This way, you can still demonstrate the level of research you have put into your book, but you don’t have to break your narrative, and the reader gets a choice whether to read the proffered information or not.

Unnecessary scenes damage your story in several ways.

- They bore readers. Just like the way an advert break during really good film right before the climax could put off a viewer and make them change the channel, an info-dump or disjointed tangent will make them simply put the book down. Worse? It could make them avoid your other or future titles.

- Misdirection for dramatic effect. Don’t be the taxi driver who goes the long way around just because they want a bigger fare (we’ve all met at least one). Your reader is your passenger. They don’t need to know what the field they are passing looks like, or what people are doing at the side of the road unless it has something important to do with the story (disposing of what could be a body?). Deliberate red herrings are an old fashioned, cliched device and have very much gone out of fashion.

- Derail narrative. On the theme of minor-character relationship-overshare: narrative prose is not the same as a TV program where all speaking-character relationships must be visible and clear from the off. Unless the feelings your main character has towards the ever so dishy, leather clad pirate (Once Upon a Time) have a bearing on the direction of the plot (they get there eventually), they need to be left out. In Speaker for the Dead, Novinha’s love for Libo (who does not take an active role and appears mostly in reference) causes her to lock her files and hide the results of her experiments for fear that he would make the same discovery that had cost his father’s life. In this case, withholding that information did not have the desired effect, but the story would not have made sense without it. However, it could have easily been overdone, and I have seen it overdone time and time again (*cough*, Sword of Truth Series, *cough*)

- Fragment the story and distract your reader. If a scene does not fit, it can wreck the whole cohesion of the book. Keeping unnecessary scenes is like trying to add extra pieces to an already completed jigsaw puzzle just because you happen to like the colour contrast. Not only to they not add anything substantial to the picture as a whole, but they can detract from, hide, or even break up the other pieces.

Here is how to avoid these errors.

Plotter or not, once you have completed your first draft (not before) you will have to go through your novel from the perspective of a reader, but before you delete anything, save your book under a different name (2nd draft?), that way if you want to recover something you have previously deleted and paste it in a later part of the book, you will be able to.

- Mentally delete them. One by one, go through and look at every scene. Can your story survive without it, in regard to character development or plot cohesion? If so, delete it. You don’t need it.

- Sweep for opportunity-darlings. Those little nuggets of ‘narrative genius’ that occurred to you as you wrote but somehow slipped past your mental outline-guards? Get rid of them. If your story can survive without them, in regard to the criteria in the previous step, then they are gatecrashing your party, abusing the free bar, and need to be thrown out. Hint: they’ll be more common in the messy middle.

- Good use of scene structure. Here, I refer you to Ms Weiland’s guide to scene and sequel construction which can be found by following the link below. You’ll also find the Amazon.com link to her book.

Source:

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 40: Unnecessary Scenes – Helping Writers Become Authors

![Commas: when to use them and when to let them have a break.]()

by | Dec 9, 2016 | Advice, Blog

We all love them. Those little marks have the power to change the whole tone of a sentence. They have power and making good use of them is important. We’ll not go into using their often abused cousins; the apostrophe. That’s a different subject entirely has been done to death but f you would like an explanation on the rules of the apostrophe let me know. Unless you are writing a musical score for the brass section of an orchestra it’s not, contrary to popular view, correct to just chuck them in wherever you think a breath or a pause should be. The reason I’m posting this is that I find myself grinding my teeth more and more and, frankly, I just can’t afford the dental bills now.

Sad comma has been abused…

The basics.

This will be a long post so please bear with me. For the sake of brevity, I shall divide it by type with explanations and finish with a simple ‘Dos and Don’ts’ summary.

Commas come in several forms:

- Listing

- Joining

- Gapping

- Bracketing

They all have their own uses and own rules of application. They are not to simply be applied ‘wherever you might pause’. Stop that. Really. It’s as bad as not using them at all.

The One Ring Rule.

This applies to all commas, no matter their type, and bind them into a nice neat bundle. Yes, It’s a weak pun. No, I’m not sorry. Let’s get on with this shall we?

A comma is never preceded by a space, but always followed by one.

I know it’s obvious but I have seen it used this way. Poor little things left, floating in a sea of unexplained space, all by themselves.

Listing commas

These are used in lists of more than two items/people/places/actions. It can also be used to join sentences where they are connected by the word and.

Examples:

- Porthos, Aramis and Athos were Musketeers.

- German is spoken in Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

- You can fly to Bulawayo via Addis Ababa, via Harare or via Johannesburg.

- Sarah speaks German, I speak English and Magda speaks Polish.

Replacing some of these commas with the word and would sound clumsy and awkward. Three or more complete sentences can be easily combined with listing commas, (example 4), but it should be noted that there is a difference between the American and British usage of listing commas. While it is usual for a comma to precede the final and in US English this is not the case in British English. The comma is meant to be a substitute for the word and, not an addition. Look out for this as many spelling and Grammar checkers don’t pick this up. Here’s the fun exception: if it would clarify your meaning, then it is encouraged to make an exception.

“My favourite composers are Handel, Mozart, Johann Strauss, and Gilbert and Sullivan.”

Without that final comma, the statement might be unclear to someone unfamiliar with classical music. It shows that Gilbert and Sullivan worked in partnership while the others worked alone. A listing comma is also used within in list of modifiers which all refer to the same subject. There will usually be no conjunction (and) as this can be replaced by a comma without losing any sense of the subject.

It changes “This is a dark and disturbing book” to “This is a dark, disturbing book.”, and “His long and dark and glossy mane shone like a water fall.” to “His long, dark, glossy mane shone like a waterfall.”

Joining commas

There is a slight difference here. Where a listing comma removes superfluous words, this comma can join two complete sentences but only if it is paired with the suitable conjunction:

Examples:

- You must submit your essay by Friday, or it will not be graded.

- England had long been isolated in Europe, but gradually began to find allies.

- The weather today has been wet and cold, and tomorrow is due to be the same.

However, this does not mean that each time these words appear in a sentence they should automatically be preceded by a comma. One of the most common errors is the failure to observe this rule. It is also one of the easiest to avoid. Either the comma must be followed by one of the aforementioned joining words or the comma should be replaced by a semi-colon.

There are also connecting words which should never be used after a comma.

- While

- However

- Therefore

- Hence

- Consequently

- Thus

- Nevertheless

- Because

Gapping commas

Gapping commas show that one or more words have been left out when the missing word would simply repeat words used earlier in the same sentence.

Some Norwegians wanted to base their national language on the speech of the capital city; others, on the rural countryside.

The gapping comma example shows that ‘wanted to base their national language’ would have been repeated. These are not always necessary and may be left out if the sentence is clear.

Bracketing commas

These are also known as isolating commas. These have a very specific role and are the most often used. For this reason, they are also the ones most often used wrongly. There are some simple rule which can avoid this.

- Bracketing commas should always be used in pairs.

- Only use them to separate a minor interruption in the sentence which does not damage its flow.

The minor interruption should be removable without affecting the meaning. That is, the sentence should make sense without it. observation of this principle should enable you to avoid basic errors and easily self-edit your own punctuation. If you have found that you have used bracketing commas around information that cannot be removed without destroying the clarity then something is wrong. You need to bin those superfluous commas and consider rephrasing. Don’t go the Harold Ross route and throw commas at your work by the fist load.

The rules of bracketing commas can be broken down quite simply:

- A restrictive clause is required to identify the subject and is never enclosed within bracketing commas. These contain the context without which the sentence would not make sense.

- Non-restrictive clauses are not required to identify subject. These always receive bracketing commas because they merely add extra information to a sentence.

Summary

- Don’t be profligate with commas. Overuse is as bad as under-use.

- Be sure why you are using a comma. ‘Because it looks right‘ is not a good reason. If you are writing for publication you can be certain that at least one reader will notice basic errors and will care enough to point out poor punctuation in a very public review.Write as though someone who knows the rules will be reading your work. A good editor will pick these bad habits, and they are bad habits, up and call you out on them. It might be an idea to throw a few deliberate errors into your sample edit pages just to see if they spot them. If they do not bring them up, that should be an alarm.

- Only use a joining comma to combine two complete sentences, and only use it with and, or, but, yet or while.

- Don’t rely on Grammarly Don’t be lazy. Your chosen craft requires you to have at least a basic understanding of punctuation. It doesn’t have to be perfect or instinctive: that’s what fastidious weirdos like me are for. The safest bet is to learn or revise the rules, and stick to them. My own exploration of that particular ‘labour-saver’ has revealed that it cannot always distinguish between versions and often makes incorrect suggestions.

Sources

- Truss, L. (2003), ‘That’ll do, Comma‘ in Eats, Shoots and Leaves, Profile Books, London

- Trask, R. L. (), ‘Chapter 3′ in The Penguin Guide to Punctuation, Penguin, London

by | Dec 6, 2016 | Advice, Blog

Choosing an editor is not easy. The good ones have fees that could choke a horse. However, they are GOOD editors, so the fees they charge are worth it. If you can afford those fees. Unfortunately, many Indie authors just can’t break out that kind of cash.

Enter the rip off artists. They come in many levels of incompetence from authors who just want to make some side cash but don’t really know how to edit, to outright thieves who will take your money and give you nothing in return. Unfortunately, the latter kind thrives on the internet. We have all heard the stories of writers victimised by people calling themselves editors but didn’t even fix spelling mistakes, much less formatting, style, or continuity issues. As an editor myself, I am always learning and improving my craft this kind of thing makes me so angry – not least because it taints all freelance editors with the same reputation – but rest easy. This post is not an estate agent type post telling you to only trust me and ignore all those other editors. Finding the right editor for you is important.

So here are some guidelines for how to find the honest ones, pick an one, and dealing with them. Feel free to pipe up in the comments with any other suggestions I might have missed.

- Go with someone you know or who is recommended. If you can’t do that, the following steps can help.

- Do your research: collect reviews and referrals. How do they respond to complaints?

- Ask for a sample edit from the first chapter of your book, before any money changes hands. A new editor should be willing to do this to get your business, and most honest editors offer this as standard.

- Have someone you already trust and knows what they are doing, read the sample and let you know if they are good.

- Try to find one who will take a deposit up front and charges balance when the job is complete. If they demand the whole balance up front, steer clear. That said, I do expect full payment up front for small jobs (less than 10 pages =2500 words), but 50% of that is refundable if the client is not happy with my work

- Generally, I would advise you to avoid those who demand the full amount upfront. If their work is genuinely substandard –this is not the same as being unhappy about harsh feedback- do not pay the balance and demand your deposit back. New writers should be aware that it often takes several rounds of editing before your work is publishable.

- No editor can wave a magic wand and suddenly turn an unstructured first draft into a literary marvel in one go, and no reputable editor will claim to be able to. It depends entirely on the submitted work.

- Not all editors offer the same services or deal with the same type of text. You need to find out which genre they will work with and what levels they offer. I offer all four levels and am pretty much happy to edit whatever crosses my desk. Others may only deal with certain genres, or offer higher level editing. An honest editor will use your work to assess the level you are writing at and determine what the work needs. They will advise you what needs to be done, and if they are not able to offer the full scope of work required, you may find they will point you in the direction of someone who can.

- If you have ever dealt with an editor who has given you less than the quality of work promised for your money, you still have rights. A freelancer is subject to the same consumer laws as everyone else.

- You want to engage with someone who will cut deep and pick up the typos and mistakes. Remember, a good editor is on your side. A reader is not. The editor wants you to be able to publish your best work possible. You are not looking for ‘nice’. If they go too easy on you or appear to be in a rush to get to print, it can still count as bad editing. The reader will not be nice or give you the benefit of the doubt as it’s your first book. They will, at best, put your book down and never read your work again. At worst, they will leave a scathing review from wherever they bought it, and they will still never read your work again.

- A good editor will not point you at a publisher or insist that their services rely on you going with a particular press. If they do, they are probably taking a back-hander. I’m afraid you will have to do your homework for that too.

by | Nov 24, 2016 | Advice, Reblogged

Want to know the most important thing about writing dialogue in fiction? If it sounds like a conversation you’d hear in the real world, you’ve gone horribly wrong somewhere.

Seriously. The next time you’re on a crowded bus or sitting by yourself in a bustling restaurant, just listen to the two people closest to you talking. You’ll hear them…

http://www.novel-writing-help.com/writing-dialogue.html