by Anna Johnstone | Sep 14, 2017 | Blog, Service

Here it is!

I’ve now closed down the old editing blog and copied my posts across so I am only managing one website. This site allows you to send enquiries, view prices and services, as well as read news and advice on writing, editing and self-publishing, all in one place.

It also allows you to post testimonials and reviews of my service. Feel free to have a click around and explore and do let me know what you think.

by | Jun 6, 2017 | Blog

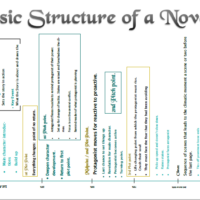

1. First draft.

This is your raw manuscript complete with typos, grammar issues. I’m assuming here that you have already outlined by this point. If you haven’t don’t worry… yet. Suffice to say, this is not the version you want to send out to anybody especially not editors. Trust me, they will not thank you for making them read this. Sending the first draft to an editor could prove extremely expensive and time-consuming, not to mention disappointing when you see how much work still has to be done.

2. Self-edit

DO NOT SKIP THIS PART.

If you have an outline already, well done. If you don’t, pay attention. You need to outline the text as it is. Once you have done this you can compare it to your previous outline and see where you have strayed or dithered from your plan. It will also show you where you can improve. Once you have applied these changes, and cannot take it further, (and run a basic spell check) then is the time to submit to an editor.

3. Alpha readers and developmental edit.

By now you should have selected a few people to give your manuscript an initial once over. Doing this and submitting the manuscript to an editor will provide reader perspective at the same time and will allow you to gauge the readability sooner rather than later. Some might find your style a little too formal for the genre, others too casual. Inappropriate tone can have a dire impact on the reception your work receives and at this stage you have time to fix it.

The developmental edit looks at your plot as a whole and guides you in how to correct it. Listen to your editor. This is not the stage to be worrying about spelling and grammar and most will not bother with it. There is no point correcting that side of things until the story is right.

Apply changes.

It is up to you to decide how you apply the advice. It’s your manuscript, just bear in mind that your editor wants your book to do as well as you do. Their job is to help you improve upon what you have, not to tell you how good it already is. Nor is it their job to write the story for you.

4. Copyedit

DO NOT MISTAKE THIS FOR THE PREVIOUS STAGE.

Copy editing is where the grammar and sentence structure is adjusted for clarity, and punctuation has been checked. It is a little more involved than proofreading but all structural issues should already have been addressed. Copy editing is very different from developmental editing. If your copyeditor is finding problems with plot, dialogue flow and characters it implies one (or more) of the following.

-

You have involved them too early. This is the most common and mostly occurs because of a fundamental misunderstanding about copyediting involves. You might be able to renegotiate the agreement from copy edit to developmental edit but bear in mind that this might well cost you more than the lower level edit. Not all editors offer higher and lower level editing, but they may be able to point you at a reliable source if they don’t.

-

You have not listened to your editor. A competent copy editor should let you know as soon as they realise that your text is not ready for them and advise you on how to go forward. When they have alerted you to the problems, go back to the notes from your developmental editor and apply the relevant changes. A good copyeditor will NOT try to get more money out of you. Nor will they offer to do both levels in one go. If you ask, they should politely decline and tell you why.

If your manuscript is less than 10k words they might continue the work and let you know of the holes. If it is more they should pause and consult you as to the direction they should take. It is important that you respond promptly to this as it could impact on your schedule if you do not. If you want them to continue working on your manuscript is it up to you to ask them and for you to ask how much more it will cost. Do not simply assume they will do it at the same rate. The SfEP recommended minimum rate for developmental editing is £30.50 per hour. For copyediting, the recommended rate is £26.50. this is because one level is more detailed and involved than the other.

-

Both.

5. Proofread.

Once you have applied the changes you will need a proofreader to go over the manuscript in detail to filter out any errors that have crept in during the last stage. Intervention here should be minimal. If your copy editor has done their job properly, nothing beyond spelling and punctuation should need to be corrected.

This is the last stage of editing. For those of you who don’t know, it gets its name from the phrase ‘galley proof’ which would be the final copy presented to the typesetter prior to printing. It’s really the last chance to correct typos and other little errors.

6. Write blurb.

By this stage you should have had a final plot in place for some time. I found that the outline I created in the self-edit helped me to write mine as it offered a readymade summary of the whole. These are not easy to write. You have spent months working on this, so how do you summarise your work into a single paragraph? There are services which will help you do this, but it might be worth asking your developmental editor for a hand. This is your elevator pitch for your story so it is worth taking the time to get it right.

7. Cover art.

Unless you are a cover designer, do not try to do this yourself. Dabbling in watercolours is not the same as being able to create a dynamic, eye-catching cover that competes with all the other covers AND reflects your book. You need to be clear about the sort of thing you need. Your designer is not a mind reader.

8. Formatting.

A minefield of technical tripwires. If you have done it before, go for it. Otherwise, use something like Vellum and get it right. I’ve not used it myself but I have heard a lot of positive things about its usability and results. The problem here is that Vellum is a MAC only piece of software and not all of us have MAC money. You can’t go wrong with the practice of finding someone who knows what they are doing and paying them for their time and effort.

9. Send out to trusted beta readers

WHO SHOULD NOT BE PICKING UP ERRORS BY THIS STAGE

The beta reading stage is a reader feedback stage only. They should not be finding errors or typos, they should not be finding plot holes or inconsistencies. The copy they read should be as near to being published as possible. Relying on readers (often unpaid) to do the job of a developmental editor is not only unwise but unfair to your readers

Finding reliable readers might be difficult to manage but writers’ critique groups might be a good place to start looking. Some betas might go quiet for no apparent reason, others might not finish the book at all. Don’t worry. Find another and remember not to approach that person in the future. This is why it is important that you select five or six people to read who can be relied upon to come back to you with valuable feedback. If you use one who charges, be sure to ask for references that you can check if you have never encountered them before. You don’t want to end up paying, only for them to disappear.

10. Publish.

This is up to you. Also, this post is not about the relative pros and cons of self vs. traditional publishing. The most important piece of advice I can offer here is that you should not be paying the publisher to print your work. They should be buying it from you. Whenever a publisher starts asking for you to pay them, walk away.

11. Give your team feedback

When you sent your work to alpha readers for a sample response you did so to gauge how it was received, so you knew how to improve upon it. The same applies to other creative industries. They are not looking for an essay on their services, just a thank you for their time and some pointers on what they did well and how they can improve. Whether editors, cover artists, formatters or readers, it is vital that you offer them feedback. They don’t know how they’ve done unless you tell them, and a good review, or recommendation or two doesn’t go amiss either. These days, simply paying the invoice and disappearing is not sufficient to let people know they have done the job well. Failure to offer feedback can often be taken as a negative response to their work.

by | Apr 7, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Proofreading and copyediting, while not nearly as entertaining as the writing process to some (a lot of us quite enjoy it), is still important. For many authors who don’t outline editing is a chance to iron out plot holes and check character arcs. For others, it’s a chance to flesh out some parts you might rush through just to finally finish creating the bones of the story but that’s the bigger picture. This post covers some of the reasons why DIY editing, is not always a good idea. There is no substitute for properly and carefully checking your own work for errors or, if the mere idea of proofreading sends you straight to the Land of Nod, hiring someone like me.

1. It won’t catch caption errors, transpositions, inconsistent formatting or repeated text.

There is no way around it. So long as you’ve spelled each individual word correctly, it will not bring it up. The red and blue squiggly things in Word are a guide but they are only as reliable as to human being who programmed them. A spellcheck is set to look for individual words but it doesn’t always see them in context. Typing ‘form’ instead of ‘from’ won’t be picked up as an error. A spell checker is no substitute for knowing the rules of grammar and punctuation. How will you know if the suggested change is correct if you don’t understand how commas work in the first place. You’ll never catch every mistake on your own, but you have a good chance of creating some new ones if you rely solely on the automatic functions of your word processor.

2. Proofreading is more than a manual spell-check.

This is the last stage of editing prior to publication. It’s vital not to leave this stage to chance. It allows you to look for colour variations, layout issues, spacing, typeface consistency, missing items, tense and tone errors, content errors, inconsistent capitalisation, that page numbers are correct, and other formatting problems. In short, this is your polish. No matter the content, presentation matters and sloppy presentation will come back to haunt you.

3. It can’t check for flow, or that the language style suits your audience.

It won’t be able to tell whether your content delivers the content promised in the title. Does the writing style of the meet their expectations? Are the facts correct? If it’s an academic work, are those facts supported by cited evidence? If my spellchecker had been able to check references, I would have had a lot fewer headaches while I was studying for my degree but I would have still checked them for errors myself.

4. It cannot fact-check.

Given enough time to do their homework, a good writer should be able to write about anything. Problems occur when guessing comes in and spellcheck won’t be able to check for accuracy, homophones, mixed metaphors or awkward similes.

5. Over-familiarity with the text.

You’ve been staring at your essay for days. Constructing arguments, deconstructing sources, and now you are finally able to submit your assignment to your tutor. This is the trouble. You will read what you expect to see on the page and this will lead to errors being missed. Even leaving it for a few days will not entirely eliminate this problem. Human memory cannot be trusted. This reason alone is reason enough to recruit an extra pair of eyes. Couple this with the limited ability of your average built-in spell-checker and you have the ideal conditions for missing some very embarrassing gaffes.

by | Nov 24, 2016 | Blog, Courses

Rayne Hall, for those not familiar with her, is a horror writer but she also writes some very helpful writing-guides. The subjects of these vary between marketing ideas, advice on how to write specific scenes, and how to self-edit (all very helpful to new writers or those who fancy a change of genre). You’ll still need an editor. Even editors use editors.

Now she is offering a free workbook when you sign up to the mailing-list. Be aware that it might take a day to come through so make sure you have the email address (from the confirmation) on your safe-senders list or it will end up in the junk file.

What is it?

This is a twenty-six-page collection of fifteen individual writing exercises, aimed to develop your own voice within your existing work. These exercises are very helpful and will aid you in your self-editing process. By all means allow your favourite authors to influence your work, there is even an exercise to pick your top five (harder than you think to narrow down: I came up with ten on the spot), but the idea is to emulate, not imitate. This will be a great help to new writers, and those who want to improve their work.

by | Oct 23, 2016 | Advice, Blog

Introduction

Below follows a checklist of advice for new authors who are thinking about approaching an editor before publication. In writing this I hope to help authors avoid some of the potential pitfalls and later disappointment when their edited work comes back to them.

Write what you know, research what you don’t.

If you are in any doubt about certain details look them up, take copious notes, and use them. Do not guess and do not attempt to fudge through the manuscript, making details up as you go along. In long pieces, fudging details will result in plot inconsistencies which will be obvious to a reader and put them off reading any more of your work. This is important when dealing with any genre but do not panic.

Use your first draft to guide your second by going through it and making a note of where you guessed details. It will require a great deal of time and honesty on your part but the end result will be worth the effort. There are a huge number of writing guides available on the market to help guide you in your research. I will provide a list of suggestions for sources and guides at the end of this post.

Use an outline.

This will help you to avoid plot inconsistencies. If you don’t have one, make one. This will provide a frame upon which you hang your story. For instance, if your main character is a PI and was last seen tailing their mark through the back alleys of Shanghai, you cannot have them, in the next chapter, and only two hours later, sunning themselves on a beach in California, having forgotten key details about their job. An outline will help you organise your story into general points. Get yourself a massive block of drawing paper (A1 or A2 if you can), some felt tips, and some big and brightly coloured post-it notes to write your ideas on and mind map it. Once you are happy with it, drag out the blue tac to fix those notes down (you don’t them falling off) and pin that outline where you can see it. Then if you have an idea later on in the writing process consult your outline before just writing it in. Does it really fit the narrative? If it doesn’t, you will have saved yourself a great deal of work. If it does, you will be able to see how to weave in your ends and not have them trailing from your finished piece (forgive the textiles analogy).

Make sure your storyline is clear and all action is relevant, driving your story.

Quantity is not the same as quality. The minutiae of opening doors and sitting to tables is not needed. If it has nothing to do with the plot such as a character slamming a door to demonstrate a bad temper or obstruct an attacker, or searching a room for an object, leave it out.

Make sure your main characters are prominent and well fleshed out.

Don’t be tempted to introduce too many main protagonists, or add them as you go along. Use your outline to help you consider which characters you will need and keep it to a minimum. If there are too many, you risk upstaging your protagonist. Again, this can be fixed if you have already started, or completed your first draft. Go through it chapter by chapter and consider whether their action is in character. Can it be

To be believable, characters must be multi-faceted and nuanced. Make their wants and needs clear. Even in fantasy, nobody is either all good, or all bad. ‘Good’ characters are not flawless. What makes them interesting is how they overcome those flaws. Nor are ‘bad’ character’s all bad. Everyone has reasons for acting the way they do and these must be made clear to your audience. However, these do not have to be revealed all in one go. For instance, the Evil Queen in the TV series Once Upon a Time, acted out of revenge against Snow White whom she felt was the party responsible for the death of the young man she actually loved. She was then manipulated, by her power-hungry mother, into a loveless marriage to a man three times her age just because he was a king. The Evil Queen became consumed by her grief and went on a murderous and devastating campaign to revenge herself against the cause of that pain. The series opened with the promise ‘to destroy the happiness’ of everyone in attendance of the wedding of Snow and Prince Charming, and worked back, revealing Regina’s path to that moment.

In Orson Scott Card’s ‘Speaker for the Dead’, (if you have not read this, I recommend you do) the now adult Andrew Wiggin having discovered the enormity of what he had done as a child, had never returned to earth. His own fictional work ‘The Hive Queen’ and the ‘Hegemon’ had reduced the name ‘Ender’ from a symbol of heroism and saviour of humanity, to an epithet ‘Ender the xenocide’. These books told the whole truth of the situations of the people about which they were written with nothing hidden. The Speakers were not there to give either vilifying post-mortem expose’s or shining accolades, but to give a true accounting of the life of the dead with all their flaws and virtues laid out. This is how to treat your characterisation.

Individual character bios could help you to get to know them and an even better perk, is that they can be updated for use in sequels or series. Don’t go into too much depth with these though, especially with characters’ physical appearance. You don’t want to end up bogged down in small details, but it will enable you to refer back to earlier books if you have crib to work from. Index cards are a very easy way to do this. If you are feeling especially adventurous, a character database would also be useful.

Is your setting well defined and clear to the reader?

Whether you are writing a Sci-fi novel or a work of Historical fiction, your world and setting has to be clear to the reader (more so for the latter than the former). Your world needs physical rules which will in turn place limitations on action, you can’t have a crusading knight whipping out a smartphone to take a selfie with Edessa burning in the background (Okay, a time-travelling knight could possibly manage this, but why?). Be clear before you start. When does your story happen? Where does it take place? How does location effect the action of the story? Knowing these details, and working them into the narrative will help bring your world to life. If it is vague and non-specific you will struggle to maintain the interest of the reader AND you will run into the issue of inconsistency within your narrative.

Do not submit a first draft to an editor.

Just don’t. Do not do it. You may feel hugely relieved to have ‘finished’ your manuscript but unless you have undergone a process of honest and critical self-editing and revision, it is not really ‘finished’. It can take several months for an editor to work through a novel and you will be very disappointed if after going through that often costly process, your story is not ready for publishing. Editing is a necessity within the creative writing process, but there is only so much it can do. An editor cannot rewrite huge chunks of your work, and most of them won’t. An editor will not do the work for you, only so you can publish in your own name. If you want a research assistant or a ghost-writer to help, you will have to recruit and pay one. The developmental and stylistic editors’ role is to look at the work you have produced and suggest (not make) the changes they feel will improve the work. Copyediting and proofreading will only look at the clarity and clear-up typographical errors. An editor will not rewrite large chunks of your work but a good one will tell you what they like and how to improve what they don’t. Listen to their advice.

That said, there is nothing to stop you from joining a writer’s group to get feedback. Bear in mind though, many members of these groups are in the same boat as you: unpublished new authors, and they are human. I wouldn’t say to simply ‘ignore the negative comments’ or dismiss constructive critique as merely ‘negativity’ from competing authors. This feedback can be very valuable. It can point you in a direction you had not originally thought of taking your narrative, or give you other ideas which help drive your story. If you take this advice, do remember who offered it in the acknowledgements. It’s only polite.