![How to be a good client.]()

by | Mar 26, 2017 | Advice, Blog

We’ve all heard of that one person who demands more from a service than is strictly reasonable, haven’t we? They want the dry cleaner to somehow get the turmeric stains off of the front of their favourite top and then scream blue murder if they – unsurprisingly – fail. They expect freebies, discounts, and are rude to waiters. They delay paying a bill for something because they’d rather go down the pub. They’d even go so far as to make a spurious complaint on the off-chance that they could save a few quid, never mind the effect that complaint could have on another person. Okay. These are extreme examples. The point is that while we expect to get our money’s worth out of a service, a healthy business relationship is a two-way street. In light of this, here are a few things to bear in mind in order to not be that customer.

Always prepare a brief.

We love these. These tell us exactly what is expected of us and enable us to realistically price and plan your project. A brief to an editor should include the following information.

- The title of the work and the author’s name and contact details.

- How many files are involved and what they include.

- The nature of the work. Is it a novel, an essay for assessment, an article for a magazine etc.? This helps us assess if we have the necessary skills to complete your project. Some editors specialise in fiction in a particular genre so sending them your dissertation on the history of the paperclip (gripping material) would not do you a lot of good.

- The deadline and when you expect the project to begin. This editor might not be available at the time you need them. If you ask, they might be able to point you in the direction of someone who is not only available but shares your obsession with stationery.

- The length of the document. This will affect the pricing of the document. Your editor needs to factor their time into the equation.

- Is it a blind edit? If the document has undergone editing prior to your project, you may want to send the original as well as other documents so that this editor can see what changes have already been made. You don’t want them undoing the work of another. It’s a waste of their time and yours.

- The style guide or house style you are working from. Send them a copy so they can familiarise themselves before starting work.

- The level of intervention expected. Don’t be the client that asks for a copy edit but expects the whole thing to be rewritten. This part of the brief allows the editor to clarify which parts are part of the normal service and which bits are extras. You will be expected to either sacrifice extras or pay for them. Similarly, you might only want to check for spelling, grammar and typos.

Your editor has many talents, but mind reading is not one of them. The brief above is the bare minimum of the information you should expect to provide. Being clear from the beginning will help avoid any nasty surprises later on. It will save you both time,

The price may be negotiable but an agreement is an agreement.

Many editors now will issue a service agreement relating to the final negotiated terms of payment. These include the services expected, sometimes in great detail, so be sure to read them thoroughly before sign anything. It also includes the rate that you have agreed to. This agreement stage protects you as much as the editor but while it constitutes a promise to carry out x, y, z, it also constitutes a promise from you to treat the service provider fairly.

A service agreement will, at the very least, include the rate that you have agreed to pay, the services to be carried out, deadlines, and the dates by which it is to be paid. You might have arranged an instalment plan. If so, you have a responsibility to make these scheduled payments at the agreed time. It will likely list any penalties and consequences for not meeting your side, as well as what they are prepared to do in the event that they fail to fulfil their end. If you do not feel these are fair then you should not sign the agreement. Attempt to negociate terms but be fair. You cannot expect them to remove anything that protects them.

Asking for extras mid-project is another danger area. For instance, if you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, would you not? The rule is the same for services. If you want extra, this may often mean amending and signing the service agreement to reflect the changes. You can be a good client by

- Asking if it is feasible to extend the length of the project. Your editor may not have the time. Some of us work on more than one project at once while others prefer to concentrate on one project at a time. We all work differently so you should double check that we are available before giving us extra work.

- Ask how much extra it will cost. If you went to a local store to collect and pay for your paperclip order but, on the way, decided you wanted bulldog clips instead, you would expect to pay the bulldog clip price, wouldn’t you? The same applies to services. Similarly, if you found that you had left something out of your brief, and it hasn’t been done, you would not complain that the editor did not fulfil your brief.

- Paying as promised and on time.

Trust

This works on both sides. You need to trust that your editor knows what they are doing and that they can deliver the service to the promised standard. They need to trust that you will uphold your end of the bargain. No matter who much you like an editor, if they feel that you have acted unfairly, they may decide that the stress of working with you is not worth the price.

You chose your editor because they possess a skill set that you do not. For this reason, alone you should listen to them. Give them the freedom to keep their promises to you. Editing is a collaborative process which takes both time and care. If they come to you with a query, answer it promptly and politely. It is true that anybody can call themselves an editor, and unfortunately there are cowboys and charlatans in every walk of life, but the good ones know their craft. Treasure them. Many are published authors in their own right so have experience from both sides of the relationship and empathise with your anxiety. They also take pride in their work and want to help you make the best of your work. It’s not just about making money.

Professional pride

Like other services, our living relies upon our reputations. There is a fine balance between personal opinion and the decisions formed by experience and skill. If your editor feels they are unable to point out flaws in your writing, due to the reaction it might induce, they will not be working to your best advantage. You want your editor to pick up problems and bad habits. It’s how you will learn to be a better writer. So while an editor might exceed their remit in some cases, remember they are doing the job to the level that they would eexpectto receive it.

Back to the dissertation analogy here. Say you handed them your brief to check spelling and punctuation only, but the editor noticed that your use of paperclip vs. paper-clip was inconsistent, but because they had not raised the issue or highlighted them, you were marked down by your tutor. And what if the reason they had not mentioned anything is becasue you had refused to accept input over the wording. This would not be what the editor would regard as a successful outcome even if they had fulfilled the terms of the brief to the lettter. This can be avoided by

- Being flexible with your brief. If you have left something off and the editor raises the issue, it is usually because some part of your writing has raised a concern and they could not, in good conscience return the editied work without raisning the issue. This is a good thing.

- Ensuring your brief includes everything you want from the service. It is also way the pre-project discussions are so important.

Reasonable deadlines

It doesn’t matter how fast someone reads...Scratch that. It matters a lot.

Proofreading, in particular, means slowing… right… down… and taking in every word carefully. It means looking for extra tall lettters hidden with others, because the human eye is a lazy beastie and will assume that what it sees is what is really there. Reading a two hundred page novel might be possible in two or three days, but editing is not the same as reading for pleasure. Often, it means checking that all captions match images and bibliography formats are correct, looking for double spacing, transpositions, or repeated text. In other words, it means doing what the spell-checker can’t do; apply common sense. This is also why you shouldn’t just forgo editors and rely on the spell check. The spell check can’t find plot holes. It is vital that you apply common sense and allow adequate time for the work to be carried out. A betaread of a 85k word novel could easily take two weeks due to the level of care needed in the reading.

Leave fair and honest feedback; spread the word

If you are happy with the service you have recieved then say so. Frequently. Recommend them to colleagues and friends. Way back before the internet, businesses lived and died on their reputations. Today, this is even mor the case. The rise of social media means that the lack of pressence and reviews is almost as bad as negative reviews. It tells future clients that this person cannot deliver what they promise. It’s like the boss who ‘loves’ you right up until you leave, then refuses to give you a reference. Reviews are the references of the information age. Use them. Tell the world you love your editor and why.

The other thing not to do is to leave vaugue feedback, or comments which contradict your repsonses to the editor. The feedback is not the place to bring up new problems. It is the place to tell people how well your editor did their job including dealing with a misunderstanding over style. Your editor relies on feedback to not only gauge reach and reception, but to iprove their service. It is important they these be honest. A dishonest negative review can do someone real harm, they are not funny or ethical. If your editor has failed to meet a deadline or fulfil their side of the agreement, AND THEN failed to deal with the situation adequately, then by all means take to their facebook page and lambast away. At least initially, you should deal with greivances calmly and in private.

by | Feb 20, 2017 | Blog

Update: 6th March 2017

Sadly, due to lack of takers, this event has had to be cancelled.

A couple of months ago I was kindly invited by another editor if I would be interested in attending a small but intensive writing workshop in Paris. Obviously, I jumped at the chance. It’s Paris! However, this isn’t the only reason I can’t wait to go (no, not the wine. Well, not entirely). What I am really excited about is the opportunity this trip will offer to learn from other writers and editors and improve the service I offer. I will admit I am a bit of a fangirl but with good reason. I have two courses on my Udemy account. Both of them are his and have been hugely helpful. His YouYube channel is another invaluable resource for new writers. The other guests have been carefully selected in order to provide expertise and insight into the writing process. It will provide a face-to-face forum for authors to take part in open discussion, storytelling, exercises and games.

Here’s the really good news: there are still four places left as far as I know. All you have to do is email Harry with the reason you want to be there. The details can be found on Harry’s website. The weekend will stretch from the 25th to the 26th May 2017. Booking will only remain open until the end of February so do hurry. ‘Inspiration and Games’ costs €200 for two nights. If you want to arrive on the 25th (which is what I am doing because the return flights from sunny Luton are a good deal cheaper on the 25th) and spend an extra day in Paris, it’s €225. This covers accommodation, two evening meals and breakfast (excluding the evening of the 25th and breakfast on the 26th).

by | Jan 20, 2017 | Advice, Blog

Writer’s First Rule.

People pay you for your work. Not the other way around. If someone asks you to pay money, ANY money, in order represent your work you need to do several things:

- Tell them you are no longer interested

- Block their number

- Add their email to your ‘blocked senders’ list

Preditors & Editors was an excellent source list of the good, the bad, and the evil in the world of writing services, but unfortunately, it appears to no longer be active.

The advance.

The sum that the publisher pays you which reflects expected sales. Unless you break the contract that’s yours regardless of how well your book sells

Earn-out

Well done. Your book has earned back your advance and then some. You now get to keep your royalties.

Rights

This is the permission you give to the publisher to publish your work in a specific form, language and place. A legitimate publisher will pay you for these rights as part of your contract, but not on a permanent basis. At the end of a set term they revert to you and if that publisher wants them back, they have to pay again. Do not sign any contract which gives the ‘publisher’ permanent rights.

Royalties

A payment structure which offers a percentage of each sale to you. An average figure would be 6-9% for paperback and 10-12% for a hardback. Ebooks earn a whopping 25%. Often the rate increases as more are sold. It is vital that you get a regular statement for these.

Getting paid

The publisher will give you an advance based on what they think they can sell, then royalties on each copy sold. If you have an agent, you will have to pay a small percentage in return for representation. Your royalties should be paid on at least a six-monthly basis from a large publishing house. Smaller ones may have a shorter schedule.

A £10k advance (lucky you) to sell your hardback novel at £10 each at a rate of 10% would earn the writer £1 per copy. They would have to sell 10,000 copies to earn out that advance. Selling anything over 10k copies is when they start paying you the rate switches around and the publisher gets £1 per copy.

Writer’s Second Rule

The agent only gets paid based on what you sell. You do not pay an agent to represent you. 15% is about average. and they don’t get paid until you do.

There may be odd business tax expenses that you need to take care of but these are infrequent and not the same as fees.

What are agents for?

- Handling contract negotiations

- Submissions of manuscripts to editors. Many of the big publishers do not accept manuscripts without an agent. You may struggle with this without an agent.

- Career advice

- Troubleshooting any problems between publisher or editor and you.

- Handling foreign rights, TV, film etc.

- Some might offer editorial assistance

How involved the get will depend entirely on the agent. Always be sure about what you want, and that they are prepared to provide it. If they want 15% of your hard earned royalty, they must earn it. Whether you opt for an agent is entirely up to you. Do not be tricked into believing you must have one for ‘legal reasons’. Anyone can hire a solicitor to look over a contract, but this is a one-off expense and it won’t mean giving up 15% of your sales.

How do I catch one?

You will need to write a convincing query letter along with a sample of the manuscript. Remember the agent won’t get paid unless it sells, they are going to need to be convinced that their time and effort won’t be wasted on a dead-parrot. If an agent accepts straight away or asks for a fee, walk away.

Writer’s Third Rule

Never pay a publisher. A publisher’s role is to print and sell books. The honest ones pay writers to produce work to print. If they ask you for money, run away. These publishers either have no ability or intention to provide marketing or distribution because you have already given them what they are looking for. Money. You would be better off doing it for free on Amazon, a free WordPress blog to serve as an author website, a free facebook page and a twitter account. Be aware that self-marketing without paid advertising is very time consuming and labour intensive (take it from someone who has been working their socks off trying to get a new start-up off the ground for the best part of a year).

Editors.

- Hired by a publishing house to buy the manuscripts for print and sale, or

- Freelancers who help writers get their work to a level where it is fit to be published.

Publishers’ editors are paid by the publishing house, not you, and will work with you until they are happy that the work is saleable. They are responsible for the quality of the finished product.

I am in box number 2. We’re hired by writers to help get your work to a standard where it can be sold. On average you can expect to pay between £25 and £100 per hour for their time and skill. Many of us prefer to charge by word count as it is never clear how much work will be needed on an individual manuscript. If you are looking to publish traditionally, you do not need to hire an editor to get the book ‘ready’ as the in-house editor will do that, but you will need to be certain that the work is of a professional quality. The publishing house should not be asking you for any money to do this work.

If you are looking to publish traditionally, you do not need to hire an editor to get the book ‘ready’ as the in-house editor will do that, but you will need to be certain that the work is of a professional quality. The publishing house should not be asking you for any money to do this work. If you are looking into self-publishing, then an editor is a must. A bad or cheap edit will stand out a mile.

You are not looking for cheap here either. Look at testimonials, look at their websites etc. If they are dirt cheap and have no testimonials, there will be a good reason. If a freelance editor demands more than a 50% upfront deposit, do not hire them.If they don’t offer free samples or refuse to offer a service agreement, these are also red flags.

Self-publishing is not the same as ‘vanity-press’.

Thankfully the stigma of self-publishing has somewhat decreased in recent years, and it has been made easy what with the rise of Amazon Kindle, iBooks, Kobo, Smashwords and Createspace et al. which are generally free except in terms of time and effort. Traditional publishing has been known to take in excess of a year to get books from the author to the page and into the shops. The cost of self-publishing comes in the fact that you are in charge of your own cover, editing, marketing etc. There are also no advances. On the other hand, royalties are paid monthly, come at around 70%, you retain all the rights. It is very important to read all of the terms and conditions before signing up to any of these services. Exclusivity deals, while on the surface might look fruitful but be aware that in recent weeks Amazon has been known to delete whole accounts on the basis of a suspicion. You will have to look carefully into all your options before deciding which route to take.

Sources

More on editors etc.

by | Jan 11, 2017 | Advice, Blog

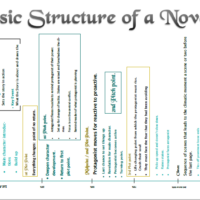

The advice in this post is just so marvellous I have just purchased her book on story structure and the accompanying workbook. Ms Weiland offers succinct advice not only on what to avoid, as well as why to avoid it and what it does to your narrative. I honestly could not have put it better. Rather than rehash the whole article I will summarise her main points, add my own input and examples, and link back to the original at the bottom.

Shall we begin?

The breadth of description required of written prose is vast in comparison with visual media. However, the author is both guide and gatekeeper to the narrative description, deciding what the reader needs to know and when. Authors are also human and, as such, we like to play with the details and show off. This is true whether we write for fun or publication. The fact remains that if we wish our writing to improve there are four habits we must consciously learn to avoid.

- Looking too deeply at the relationships between minor characters. However close the attachment, or tense the conflict, the relationship between the minor players need not get a mention unless it has an effect on the plot. if you want to explore it further you can always take a leaf out of the likes of Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Shadow) or Anne McCaffrey (Nerilka’s Story) who have written whole versions of their works from the perspective of minor characters

- Travelling filler and uneventful journeys. Don’t try to stage direct an empty theatre: you’ll bore yourself as well as your audience.

- Repetition of conversations already witnessed. Say you were at a party, but one of the guests was reciting back to you a discussion you had already heard. You’d get bored pretty quickly right? So will your readers.

- Information-dumping. If you have found out something really interesting, and you just have to share it, use an end note (not the same as a footnote). It’s what they’re for. This way, you can still demonstrate the level of research you have put into your book, but you don’t have to break your narrative, and the reader gets a choice whether to read the proffered information or not.

Unnecessary scenes damage your story in several ways.

- They bore readers. Just like the way an advert break during really good film right before the climax could put off a viewer and make them change the channel, an info-dump or disjointed tangent will make them simply put the book down. Worse? It could make them avoid your other or future titles.

- Misdirection for dramatic effect. Don’t be the taxi driver who goes the long way around just because they want a bigger fare (we’ve all met at least one). Your reader is your passenger. They don’t need to know what the field they are passing looks like, or what people are doing at the side of the road unless it has something important to do with the story (disposing of what could be a body?). Deliberate red herrings are an old fashioned, cliched device and have very much gone out of fashion.

- Derail narrative. On the theme of minor-character relationship-overshare: narrative prose is not the same as a TV program where all speaking-character relationships must be visible and clear from the off. Unless the feelings your main character has towards the ever so dishy, leather clad pirate (Once Upon a Time) have a bearing on the direction of the plot (they get there eventually), they need to be left out. In Speaker for the Dead, Novinha’s love for Libo (who does not take an active role and appears mostly in reference) causes her to lock her files and hide the results of her experiments for fear that he would make the same discovery that had cost his father’s life. In this case, withholding that information did not have the desired effect, but the story would not have made sense without it. However, it could have easily been overdone, and I have seen it overdone time and time again (*cough*, Sword of Truth Series, *cough*)

- Fragment the story and distract your reader. If a scene does not fit, it can wreck the whole cohesion of the book. Keeping unnecessary scenes is like trying to add extra pieces to an already completed jigsaw puzzle just because you happen to like the colour contrast. Not only to they not add anything substantial to the picture as a whole, but they can detract from, hide, or even break up the other pieces.

Here is how to avoid these errors.

Plotter or not, once you have completed your first draft (not before) you will have to go through your novel from the perspective of a reader, but before you delete anything, save your book under a different name (2nd draft?), that way if you want to recover something you have previously deleted and paste it in a later part of the book, you will be able to.

- Mentally delete them. One by one, go through and look at every scene. Can your story survive without it, in regard to character development or plot cohesion? If so, delete it. You don’t need it.

- Sweep for opportunity-darlings. Those little nuggets of ‘narrative genius’ that occurred to you as you wrote but somehow slipped past your mental outline-guards? Get rid of them. If your story can survive without them, in regard to the criteria in the previous step, then they are gatecrashing your party, abusing the free bar, and need to be thrown out. Hint: they’ll be more common in the messy middle.

- Good use of scene structure. Here, I refer you to Ms Weiland’s guide to scene and sequel construction which can be found by following the link below. You’ll also find the Amazon.com link to her book.

Source:

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 40: Unnecessary Scenes – Helping Writers Become Authors

by | Dec 6, 2016 | Advice, Blog

Choosing an editor is not easy. The good ones have fees that could choke a horse. However, they are GOOD editors, so the fees they charge are worth it. If you can afford those fees. Unfortunately, many Indie authors just can’t break out that kind of cash.

Enter the rip off artists. They come in many levels of incompetence from authors who just want to make some side cash but don’t really know how to edit, to outright thieves who will take your money and give you nothing in return. Unfortunately, the latter kind thrives on the internet. We have all heard the stories of writers victimised by people calling themselves editors but didn’t even fix spelling mistakes, much less formatting, style, or continuity issues. As an editor myself, I am always learning and improving my craft this kind of thing makes me so angry – not least because it taints all freelance editors with the same reputation – but rest easy. This post is not an estate agent type post telling you to only trust me and ignore all those other editors. Finding the right editor for you is important.

So here are some guidelines for how to find the honest ones, pick an one, and dealing with them. Feel free to pipe up in the comments with any other suggestions I might have missed.

- Go with someone you know or who is recommended. If you can’t do that, the following steps can help.

- Do your research: collect reviews and referrals. How do they respond to complaints?

- Ask for a sample edit from the first chapter of your book, before any money changes hands. A new editor should be willing to do this to get your business, and most honest editors offer this as standard.

- Have someone you already trust and knows what they are doing, read the sample and let you know if they are good.

- Try to find one who will take a deposit up front and charges balance when the job is complete. If they demand the whole balance up front, steer clear. That said, I do expect full payment up front for small jobs (less than 10 pages =2500 words), but 50% of that is refundable if the client is not happy with my work

- Generally, I would advise you to avoid those who demand the full amount upfront. If their work is genuinely substandard –this is not the same as being unhappy about harsh feedback- do not pay the balance and demand your deposit back. New writers should be aware that it often takes several rounds of editing before your work is publishable.

- No editor can wave a magic wand and suddenly turn an unstructured first draft into a literary marvel in one go, and no reputable editor will claim to be able to. It depends entirely on the submitted work.

- Not all editors offer the same services or deal with the same type of text. You need to find out which genre they will work with and what levels they offer. I offer all four levels and am pretty much happy to edit whatever crosses my desk. Others may only deal with certain genres, or offer higher level editing. An honest editor will use your work to assess the level you are writing at and determine what the work needs. They will advise you what needs to be done, and if they are not able to offer the full scope of work required, you may find they will point you in the direction of someone who can.

- If you have ever dealt with an editor who has given you less than the quality of work promised for your money, you still have rights. A freelancer is subject to the same consumer laws as everyone else.

- You want to engage with someone who will cut deep and pick up the typos and mistakes. Remember, a good editor is on your side. A reader is not. The editor wants you to be able to publish your best work possible. You are not looking for ‘nice’. If they go too easy on you or appear to be in a rush to get to print, it can still count as bad editing. The reader will not be nice or give you the benefit of the doubt as it’s your first book. They will, at best, put your book down and never read your work again. At worst, they will leave a scathing review from wherever they bought it, and they will still never read your work again.

- A good editor will not point you at a publisher or insist that their services rely on you going with a particular press. If they do, they are probably taking a back-hander. I’m afraid you will have to do your homework for that too.