by Michelle Dunbar Editing Solutions | Oct 26, 2016 | Advice, Blog, Uncategorized

Having spent months, and possibly years on your manuscript, writing, editing, rewriting, editing, and then tweaking it a few more times for good measure, the time will come when the services of an editor will be required. But with so many editors to choose from, all with a wide range of pricing and experience, how do you work out who to hire?

And where do you even begin?

My advice, first of all, would be to seek out the personal recommendations of your fellow authors. Some may have been lucky enough to have found an affordable, yet excellent editor.

Armed with a short list of names to consider, you should take the time to visit each of the editor’s websites with a view to finding answers to the following:

- Do they offer the editing service you are looking for?

- Are they experienced in the editing service you are looking for?

- Do they have a good knowledge of your chosen genre?

- What does the editor charge? (Please note that not all editors list their prices on their website)

- Do they have testimonials/reviews you can read?

- Your initial impression of their website? Does the editor seem organised? Professional? Is their website in disarray and littered with typos?

- Do they offer free sample edits?

With some of your questions answered, and a chosen editor in mind, it’s time to make ‘first contact’ so you can continue your assessment of them.

Introduce yourself, the genre and word count of your manuscript, what editing package you are considering, and enquire about sending them an excerpt of your manuscript for a sample edit. When engaging in communication, consider their level of professionalism and knowledge, as well as their response time. Do they reply within 24/48 hours or are you left hanging on for days? Initial communication can be a good indicator of what to expect if you hire this editor.

I cannot stress enough how important it is to find an editor who is not only experienced and knowledgeable but who you like and feel comfortable with. Likewise, the editor needs to feel comfortable about working with you too. Editing isn’t about going to battle over a particular scene or style of punctuation, it’s about working together with the shared aim of making your book the best it can be.

by | Oct 23, 2016 | Advice, Blog

Introduction

Below follows a checklist of advice for new authors who are thinking about approaching an editor before publication. In writing this I hope to help authors avoid some of the potential pitfalls and later disappointment when their edited work comes back to them.

Write what you know, research what you don’t.

If you are in any doubt about certain details look them up, take copious notes, and use them. Do not guess and do not attempt to fudge through the manuscript, making details up as you go along. In long pieces, fudging details will result in plot inconsistencies which will be obvious to a reader and put them off reading any more of your work. This is important when dealing with any genre but do not panic.

Use your first draft to guide your second by going through it and making a note of where you guessed details. It will require a great deal of time and honesty on your part but the end result will be worth the effort. There are a huge number of writing guides available on the market to help guide you in your research. I will provide a list of suggestions for sources and guides at the end of this post.

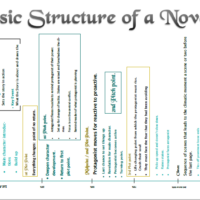

Use an outline.

This will help you to avoid plot inconsistencies. If you don’t have one, make one. This will provide a frame upon which you hang your story. For instance, if your main character is a PI and was last seen tailing their mark through the back alleys of Shanghai, you cannot have them, in the next chapter, and only two hours later, sunning themselves on a beach in California, having forgotten key details about their job. An outline will help you organise your story into general points. Get yourself a massive block of drawing paper (A1 or A2 if you can), some felt tips, and some big and brightly coloured post-it notes to write your ideas on and mind map it. Once you are happy with it, drag out the blue tac to fix those notes down (you don’t them falling off) and pin that outline where you can see it. Then if you have an idea later on in the writing process consult your outline before just writing it in. Does it really fit the narrative? If it doesn’t, you will have saved yourself a great deal of work. If it does, you will be able to see how to weave in your ends and not have them trailing from your finished piece (forgive the textiles analogy).

Make sure your storyline is clear and all action is relevant, driving your story.

Quantity is not the same as quality. The minutiae of opening doors and sitting to tables is not needed. If it has nothing to do with the plot such as a character slamming a door to demonstrate a bad temper or obstruct an attacker, or searching a room for an object, leave it out.

Make sure your main characters are prominent and well fleshed out.

Don’t be tempted to introduce too many main protagonists, or add them as you go along. Use your outline to help you consider which characters you will need and keep it to a minimum. If there are too many, you risk upstaging your protagonist. Again, this can be fixed if you have already started, or completed your first draft. Go through it chapter by chapter and consider whether their action is in character. Can it be

To be believable, characters must be multi-faceted and nuanced. Make their wants and needs clear. Even in fantasy, nobody is either all good, or all bad. ‘Good’ characters are not flawless. What makes them interesting is how they overcome those flaws. Nor are ‘bad’ character’s all bad. Everyone has reasons for acting the way they do and these must be made clear to your audience. However, these do not have to be revealed all in one go. For instance, the Evil Queen in the TV series Once Upon a Time, acted out of revenge against Snow White whom she felt was the party responsible for the death of the young man she actually loved. She was then manipulated, by her power-hungry mother, into a loveless marriage to a man three times her age just because he was a king. The Evil Queen became consumed by her grief and went on a murderous and devastating campaign to revenge herself against the cause of that pain. The series opened with the promise ‘to destroy the happiness’ of everyone in attendance of the wedding of Snow and Prince Charming, and worked back, revealing Regina’s path to that moment.

In Orson Scott Card’s ‘Speaker for the Dead’, (if you have not read this, I recommend you do) the now adult Andrew Wiggin having discovered the enormity of what he had done as a child, had never returned to earth. His own fictional work ‘The Hive Queen’ and the ‘Hegemon’ had reduced the name ‘Ender’ from a symbol of heroism and saviour of humanity, to an epithet ‘Ender the xenocide’. These books told the whole truth of the situations of the people about which they were written with nothing hidden. The Speakers were not there to give either vilifying post-mortem expose’s or shining accolades, but to give a true accounting of the life of the dead with all their flaws and virtues laid out. This is how to treat your characterisation.

Individual character bios could help you to get to know them and an even better perk, is that they can be updated for use in sequels or series. Don’t go into too much depth with these though, especially with characters’ physical appearance. You don’t want to end up bogged down in small details, but it will enable you to refer back to earlier books if you have crib to work from. Index cards are a very easy way to do this. If you are feeling especially adventurous, a character database would also be useful.

Is your setting well defined and clear to the reader?

Whether you are writing a Sci-fi novel or a work of Historical fiction, your world and setting has to be clear to the reader (more so for the latter than the former). Your world needs physical rules which will in turn place limitations on action, you can’t have a crusading knight whipping out a smartphone to take a selfie with Edessa burning in the background (Okay, a time-travelling knight could possibly manage this, but why?). Be clear before you start. When does your story happen? Where does it take place? How does location effect the action of the story? Knowing these details, and working them into the narrative will help bring your world to life. If it is vague and non-specific you will struggle to maintain the interest of the reader AND you will run into the issue of inconsistency within your narrative.

Do not submit a first draft to an editor.

Just don’t. Do not do it. You may feel hugely relieved to have ‘finished’ your manuscript but unless you have undergone a process of honest and critical self-editing and revision, it is not really ‘finished’. It can take several months for an editor to work through a novel and you will be very disappointed if after going through that often costly process, your story is not ready for publishing. Editing is a necessity within the creative writing process, but there is only so much it can do. An editor cannot rewrite huge chunks of your work, and most of them won’t. An editor will not do the work for you, only so you can publish in your own name. If you want a research assistant or a ghost-writer to help, you will have to recruit and pay one. The developmental and stylistic editors’ role is to look at the work you have produced and suggest (not make) the changes they feel will improve the work. Copyediting and proofreading will only look at the clarity and clear-up typographical errors. An editor will not rewrite large chunks of your work but a good one will tell you what they like and how to improve what they don’t. Listen to their advice.

That said, there is nothing to stop you from joining a writer’s group to get feedback. Bear in mind though, many members of these groups are in the same boat as you: unpublished new authors, and they are human. I wouldn’t say to simply ‘ignore the negative comments’ or dismiss constructive critique as merely ‘negativity’ from competing authors. This feedback can be very valuable. It can point you in a direction you had not originally thought of taking your narrative, or give you other ideas which help drive your story. If you take this advice, do remember who offered it in the acknowledgements. It’s only polite.

by | Oct 18, 2016 | Advice, Reblogged

Before you hire an editor, you need to know what kind of help you’re looking for.

http://www.writersdigest.com/online-editor/10-things-your-freelance-editor-might-not-tell-you-but-should

This post offers excellent advice to new writers. Read it. Save it. Keep referring back to it but to summarise.

- Avoid the temptation to submit a first draft. (Really never do this. Harry DeWulf has some great advice on self-editing)

- Editing and ghostwriting are not the same thing.

- Is your book in the editor’s preferred genre. (I am not fussy, my tastes are fairly eclectic but I do enjoy prophetic dystopian sci-fi).

- Critical feedback is a given. It is our job to help you improve your work.We want you to succeed.

- Writing is a hike not a sprint. It takes time to get it right so set realistic goals.

- Copy-editing and proofreading are a waste of time and money prior to addressing structure and clarity.

- Do not confuse being published with being a good writer.

- Tell your editor what you want to accomplish. It is your work, and it makes their job easier.

- Minor changes to tiny details are not revision. Don’t be afraid to discuss the feedback if you disagree with it. (See point 8).

- The editor is on your side: the reader won’t be, but remember that it is your work.